“Through literature we can learn to perceive the other, not scientifically as we would treat an object of study, but as a desire for otherness that renews the world and humanizes our differences.”

Bruno Leal interviews Berttoni Licarião

Just over a year ago, we moved from Rio de Janeiro to Brasília. Since then, here in the Federal Capital we have discovered numerous talented and versatile researchers with a lot to say. From Plano Piloto to Taguatinga and Ceilândia, the Cerrado is experiencing a moment of great vitality, perhaps unprecedented, in the cultural and literary life of the University.

One such talent is 34 year old Berttoni Cláudio Licarião. From the state of Paraiba, but living in Brasilia since 2015, he is on the final lap of his PhD in literature at the University of Brasília (UnB). Its theme: the dictatorship in contemporary Brazilian fiction. Licarião has an acclaimed (and committed) literary profile on Instagram (@literatoni), where he comments and recommends.

Bruno Leal, historian editor of Café História interviews Licarião on the Brazilian boom in military dictatorship fiction, historical-literary links, and how fiction can shape our perception of the past, particularly so-called “traumatic pasts”. According to Licarião, “aware of the dangers of silencing (after all, the first victim of dictatorships is always language), literature now presents an opportunity to grapple with our memory deficit, to find a space for mourning, so that we can escape the violent upshot of repressing ”.

In recent years, there seems to have been a wealth of fiction on the Brazilian military dictatorship. If so, how do you explain this phenomenon?

Absolutely. Whether through poems, short stories, novels, witness accounts or literary journalism, literature has been dealing with the Brazilian dictatorship since the early days of the coup in 1964, Today, we can even fit works into well-marked periods, such as, for example, the witness phase of the 1970s and 1980s, or, still more clearly, the works of resistance published under AI-5, such as “Incident at Antares” (Erico Verissimo, 1971), “Shadows of Bearded Kings” (José J. Veiga, 1972) and “The Girls “(Lygia Fagundes Telles, 1973). However, if we take current publications, plus those critically considered in the last thirty-five years, which have the dictatorship as a background or main theme, we’ll see that the last decade was one of the most productive. Amongst the 110 works that I’ve managed to catalogue so far, almost half, or fifty-three were published between 2010 and 2019.

One reason I can put forward has to do with “cycles of cultural memory”, a concept developed by the U.S. researcher Rebecca J. Atencio to describe the simultaneous appearance, either by coincidence or design, of a given work (or set of works) and institutional action which carry historical importance. Atencio pinpoints several of these cycles throughout recent Brazilian history, the first example is the coinciding of the 1979 Amnesty Law with the emergence of the narratives “What’s Up, Comrade?” by Fernando Gabeira, and “Os carbonários”, by Alfredo Sirkis, published the following year. For Atencio, analysis of the relationships between institutional mechanisms and artistic-cultural production reveals a deep and complex interaction in the construction of collective and individual memory.

From this standpoint, the work of the National Truth Commission (2012-2014) stirred up memories while giving, during the recent decade, impetus to the creation of fiction, equipping literature to settle the score between national history and collective memory. With the output from public hearings and state or national commissions allowing survivors and family members into the broader spheres of cultural production, just talking amongst themselves about the trauma of the dictatorship is no longer an option. Aware of the dangers of silencing (after all, the first victim of dictatorships is always language), literature now presents an opportunity to grapple with our memory deficit, to find a space for mourning, so that we can escape the violent upshot of repressing. In addition, the close relationship between the impunity of the dictatorship’s violence and the upsurge in police brutality seen today in Brazil directs the writer to the recent past, as a way of understanding the traces of authoritarianism that trouble our democracy.

Your thesis is provisionally entitled The State of Memory: the dictatorship in Brazilian contemporary fiction. Tell us exactly what is covered in your doctorate.

The thesis focuses on Brazilian literary treatment of the dictatorship, published in the last decade, especially since the work of the CNV, or National Truth Commission (2012-2014). Faced with the landscape of extreme violence that characterizes our entire history, the CNV represented a return of the repressed, insofar as it opened up a traumatic memory not dealt with collectively. In my reading, I believe that the last thirty-four years have been marked by a process of individualization of crimes against humanity, insofar as the country has not taken on the task of overcoming the coup of 64 as a collective trauma but left it circumscribed to personal tragedies. Therefore, our process of recovering this memory was subverted, limited, with rare exceptions, to palliative measures of retraction and compensation. The 1979 Amnesty Law contributed greatly to this normalization of forgetfulness, promoting that “erasure of error” mentioned by Paul Ricouer. Here, amnesty engendered amnesia, and the grief of each family was restricted to the private sphere, lacking retribution. Torturers remain unpunished, benefiting from “national Alzheimer’s disease” .

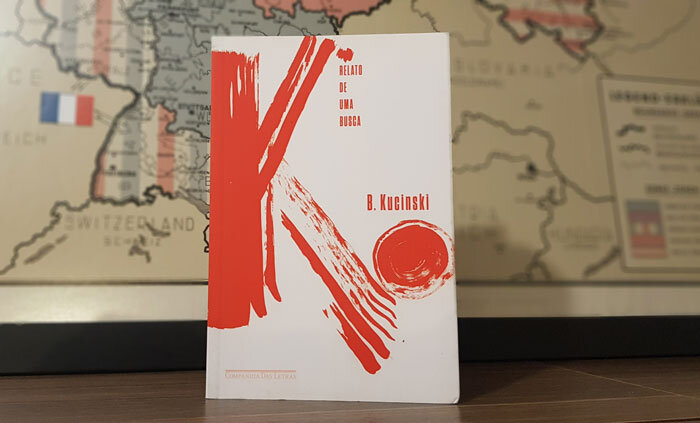

So, I’m inquiring into how the individualization of the trauma of dictatorship, as well as the policy of effacement promoted by the 1979 Amnesty Law, has been tested in recent fiction. This sample is examined from what I call our “state of memory”, a condition which sees authoritarianism as a blockage in the study corpus, transforming cultural memory, as it considers the collective experience, into a space for confrontation. The thesis presents a brief overview of the fiction published in the last decade, but it concentrates more vigorously on the works of Bernardo Kucinski , “K: Report of a Search” (2011), “You Will Return to me and Other Tales” (2014) and “The Visitors “( 2016) – and in the Infernal Trilogy of Micheliny Verunschk – comprising the novels “Aqui, no Coração do Inferno (2016), “The Weight of a Man’s Heart” (2017) and “O amor, esse obstáculo” (2018). Written after re-democratization and the opening of the Truth Commissions, these narratives represent the experience of trauma from different perspectives, defined by the degree of cruelty and extermination carried out by the repressive machine, and by the role that memory of the period plays in the country’s consciousness today.

What should we understand by the memory of dictatorship in contemporary Brazilian fiction? What can we learn from story-telling that we don’t from historiography.

Ana Miranda, the writer from Ceará, once said something that never leaves me when I discuss concepts as wide as truth, memory, fiction and history: “Historians are fictionists who pretend to be telling the truth, fictionists are historians who pretend to be telling a lie”. Apposite, because it points to the adjacency of historiographic and literary discourses: both are gestures of language, and language is always a social construction, involving class, gender, place, temporality, etc. Although the work of the historian and novelist have different objectives, every historical novel, inadvertently or intentionally, delves into human behavior, not only in the sense of the deep research required for the so-called “historical novels”, but above all because the narrative choices of a story written in 1996 about, say, the dispatch of Portuguese orphans to Brazil in 1555, tells much more about the present than the past, where the plot develops.

It is in this sense that dictatorship fiction, apart from showing the reader the techniques of the torture, arbitrariness and deception which typified Brazilian history from1964 to 1985, contributes to the perception of a falsely pacified present, mixed with cynical semi-democracy and “device for collective repressing”, in the words of writer Julián Fuks (2). As with history, literature always starts with questions from the present, but instead of delivering knowledge constructed from sources and documents, it renders for us what is human. This means that on the horizon of literature, we should not seek “truths” from the world (inasmuch that the literary text also has value as a historical document), but varied representations about the behavior of individuals and groups, as well as about the creation of institutions or of world-views. As Roland Barthes (3) succinctly puts it, fiction “does not say that it knows something, but that it knows about something” .With literature we can learn to perceive the other, not scientifically as we would an object of study, but as desire for otherness that renews the world and humanizes differences.

Has your doctoral research yielded any notable discovery ?

If, as I argue, the reality that literature pursues is that of existence, a field of human possibilities, observing how the memory of the dictatorship behaves in contemporary fiction is an opportunity to get in touch with what has been institutionally silenced. With the obvious lack of tokens, tribunals and sites to remind us, fiction provides our trauma with a complex inventory that recreates everything the historian often avoids saying: the pain and blood, tears and wounds, tension and horror. The record is hard, scarce and intimidating; literature, on the other hand, manages to be a little more accessible, fits into the hand and reaches a wider audience, often acting as a substitute for historiography. Aware of the many controversies surrounding the concepts that follow, I dare say that literature can, in this sense, be a more democratic chronicle of the Brazilian dictatorship. It is not a matter, of course, of naively bringing literature and truth together, but of understanding the former as a place where discourse on the past can be expressed.

The question is a little more difficult to answer because literature research, as a rule, depends on one or more literary texts that are already known to the researcher. There is not much space, therefore – as there is in the analysis of sources, files and documents – for the unexpected. But if we widen the scope of the research to include literature produced in other post-dictatorship Latin American countries, Brazil merits attention due to the still very strong descriptive evidence of state-sponsored torture and violence. In contexts such as Argentina, for example, which held its National Truth Commission (1983-1985) shortly after the end of the dictatorship (1976-1983), denouncing repressive violence has given way to questions about the conflict of generations and the future of memory, or even the guilt of those who survived and of those who were collaborating with the regime. Explicit scenes of torture have become less and less frequent.

In addition, the close relationship between the impunity of the dictatorship’s violence and the upsurge in police brutality seen today in Brazil directs the writer to the recent past, as a way of understanding the traces of authoritarianism that trouble our democracy.

A possible reading of the insistence of Brazilian literature to bring torture and violence to the forefront of its narratives could be due to the absence of public guidelines and legislation that would be fundamental to overcoming the national trauma. To quote the psychoanalyst Maria Rita Kehl, “To overlook torture produces the normalization of violence as a serious social symptom in Brazil”. [4] The ethical will of literature, in this case, seems attentive to the dangers of suppression. The 1979 Law of Amnesty contributed greatly to this normalization of forgetfulness, promoting that “erasure of error” mentioned by Paul Ricouer. Here, amnesty engendered amnesia, and leaving each family to grieve in private, without retribution. Torturers, as beneficiaries of “national Alzheimer’s disease”, go unpunished,

In Europe there exists a “literature of suffering” which is well-established, particularly in relation to the Holocaust. Do you feel that our own fictional treatments of the dictatorship might fit into this concept?

Literary criticism and trauma studies have been going together for some time and, like any long-standing relationship, some limits tend to be crossed, creating unease on both sides. There are those who defend, on the one hand, a clear differentiation between testimonial writing and fiction writing, and, on the other, there are those who wish to expand the concept of witness to include those who hear the story of suffering and do not go away, but, keeping the other’s narrative of torment alive, reproducing it with the means at their disposal. In the crossfire between the ethical limits of fiction and the abuse of memory, Shoah (or the Holocaust) loses its historical unambiguity to become a kind of epistemological model helping us to think about other traumatic historical processes. It is here that “trauma literature” and “dictatorship literature” come together. Within a context of violence like Brazil’s, the traumatic component of the story is seen in the narratives through different strategies: as an obstacle to identifying knowledge (of a character, of a group or of the people); as symptoms of precariousness and melancholy; as internal disconnect and discontinuity of perception; or even through recurring figures of speech such as the hyperbola and the ellipse. Through these strategies, the traumatic impact finds in fiction forms similar to the testimonies of concentration camp survivors. The fundamental difference, in the case of fiction (here in “opposition” to the testimony), is that its connection with the trauma does not presuppose the rescue of the individual from the split caused by repressing; what fiction can do is to rescue the collective unconscious from the field of inexpressible experience.

Could you suggest two books about the Brazilian military dictatorship?

Bernardo Kucinski’s “K” is always top of my listen first place in my indications because I consider him a true watershed of contemporary national literature. It is a novel that accompanies the search for a daughter and son-in-law disappeared by the dictatorship. Despite the biographical input – the author lost his sister and brother-in-law, Ana Rosa Kucinski and Wilson Silva, both kidnapped in 1974 by the police in São Paulo – the narrative is mainly a work of fiction, although the parallels between what’s real and what’s fictitious is evident from the foreword: “Dear reader: Everything in this book is an invention, but almost everything happened”. Marked by the absurd, the loss of meaning and, consequently, the negativity of the experience, the narrative combines different voices and perspectives to bring to the present an essential discussion about the institutional, affective and symbolic non-place of the disappeared activist.

The second recommendation has to be the novel “Crow Blue “(Azul Corvo), by Adriana Lisboa. Published in 2010, it is the story of a teenager who, after the death of her mother, decides to look for her biological father in the United States and ends up finding a survivor of the Araguaia guerrilla group. An episode long denied by the armed forces, the guerrillas have, for this very reason, been rarely addressed in fiction. Lisboa’s work manages to unite issues as wide and sensitive as exile, immigration, memory and identity in a fabric woven with surgical precision. Her characters, like those of Kucinski, embody a precarious national memory in search of what has been institutionally denied: justice and mourning. Both searches, in K. and Crow Blue, in the 1970s or in the 2000s, represent the hindrances and forces inherent in the discovery and transmission of a memory that is set against the amnesiac conciliation promoted by the amnesty.

Notes

[1] Bernardo Kucinski, in the chapter “The letters to the nonexistent recipient” In the book “K”.

[2] Julián Fuks. “The Post-Fiction Era: Notes on the Insufficiency of Invention in the Contemporary Novel,”. Chapter “Ethics and post-truth”, published by Dublinense, 2017.

[3] Roland Barthes in the text “Aula”, from 1977.

[4] In the article “Torture and social symptom” published in the book “O que resta da ditadura” (2010), organized by Edson Teles and Vladimir Safatle.

Berttoni Licarião is a PhD student of Literature at the University of Brasília (CAPES scholarship) researching into the memory of dictatorship in contemporary Brazilian fiction. He holds a Master’s in Literary Studies from the Federal University of Minas Gerais, specialising in Brazilian Literature. Before graduating from the Federal University of Paraíba in 2009, he he participated for two years in a social-inclusion project teaching English through Shakespeare.

Bruno Leal Pastor de teaches History at graduate and post-graduate level at the University of Brasília (UnB). He is also Editor-in-chief of Café História.

This text was translated from Portuguese by Tira Text. – UK

How to cite this interview

LICARIÃO, Berttoni. The military dictatorship in Brazilian contemporary fiction – Interview with Berttoni Licarião. In: Café História – History Made by Clicks. Available in: https://www.cafehistoria.com.br/military-dictatorship-in-brazilian-contemporary-fiction/.