Written mostly during fascist imprisonment between 1929 and 1935, the first publications of the works of the Italian thinker Antonio Gramsci arrived in Brazil only at the end of the 60s during the Civil-Military Dictatorship. At first, the publications were an editorial failure and were stuck on the shelves. In the following two decades, however, in the context of political opening and Brazilian redemocratization, Gramsci’s thought gained notoriety among various intellectuals. Intellectuals such as Fernando Henrique Cardoso, Carlos Nelson Coutinho and Luiz Werneck Vianna used the reflections of the Italian politician to think about ways to overcome authoritarianism and build a democratic society.

Despite having stimulated important analyzes during the period, Gramsci never became known to the public. In the 2010s, this began to change thanks to the growth of the far-right in Brazil. Gramsci began to be presented as one of those responsible for the advance of “leftism” and “communism” in the country. Olavo de Carvalho (1947-2022), one of the main intellectuals linked to the Brazilian far-right, claimed that Gramsci would have provided a change in communist methods to achieve revolution.

To Carvalho, unlike traditional communist leaders like Lenin, who advocated armed struggle for the construction of communist revolution, Gramsci would have established culture as a central element for social transformation. Abandoning weapons, communists should thus infiltrate media outlets, universities, and schools and, from these spaces, take over the culture of the nation, creating a silent and unconscious revolution.

This idea, besides being mistaken, is also authoritarian. The assertion that Brazil would be experiencing the nearing of a communist revolution is based on the idea that the military during the Dictatorship would not have fulfilled its main function, that is, to eliminate communists. By eliminating only those who took up arms to face the regime, the military would have allowed left-wing growth in Brazilian culture. This violent view of politics is an excrescence of anti-communist culture from the 30s and 60s, which chose Gramsci as a major threat to Western societal values. His theories, always associated with a diabolical dimension, would represent the continuity of communist threat even after the end of the Soviet Union. That is, communist danger should still be eradicated from society today.

More than in Olavo de Carvalho’s books, the demonic view of Gramsci spread through social media, Whatsapp groups and even religious services. In addition to contributing to the growth of authoritarian speeches, this mistaken understanding disqualifies one of the greatest intellectuals of the 20th century.

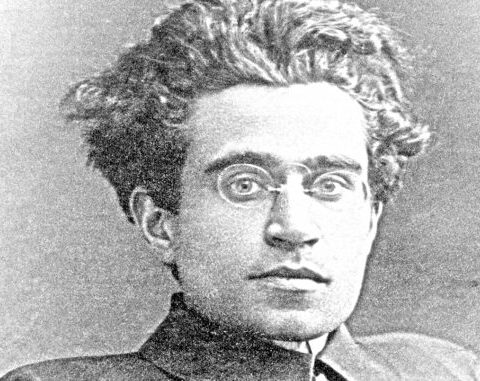

Who was Antonio Gramsci, after all?

Son of a modest family with left-wing political inclinations, Gramsci was born in 1891 in Sardinia, an island located in southern Italy. As a boy, Gramsci began to take an interest in politics and won a scholarship to attend university in Milan, in the north of the country. This change was essential for Gramsci to perceive the social and geographical inequalities of his country. While the south was marked by a predominantly agrarian economy, the north was home to the main industries of Italy at that time.

Despite not being able to finish his university studies due to financial problems, Gramsci got even closer to politics, joined the Italian Socialist Party and began writing articles for various newspapers of the time. These articles addressed the political issues of everyday Italian and world life. Therefore, as Gramsci himself said, they were texts that would be used to pack fish at the fair the next day.

The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 fascinated Gramsci, who began to think about ways to translate Bolshevik politics into Italy. In this sense, the Factory Councils, more than a group of workers to manage production in factories, were the embryos of a new Workers’ State. In transition to the 1920s, the council movement advanced strongly in Italy and produced important strikes in main Italian companies.

Despite its progress, the movement was defeated. For Gramsci, the reasons for the defeat were in the revolutionary weakness of the Italian socialists. Faced with this, together with other party members, Gramsci contributed to the foundation of the Italian Communist Party in 1921. However, in the context of the defeat of the councils, there was a strengthening of fascism and the rise of Benito Mussolini to power in 1922. At this moment, Gramsci spent a few years in Austria and Russia as a party leader and returned to Italy, being elected deputy. Even as a deputy, Gramsci was a victim of arbitrary decisions and fascist violence. In September 1926, a few months before Gramsci’s arrest, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini was the victim of an assassination attempt. The attack served as a justification for an increase in violence and for the persecution of communists. Amid persecution, Gramsci was sentenced to more than 20 years in prison.

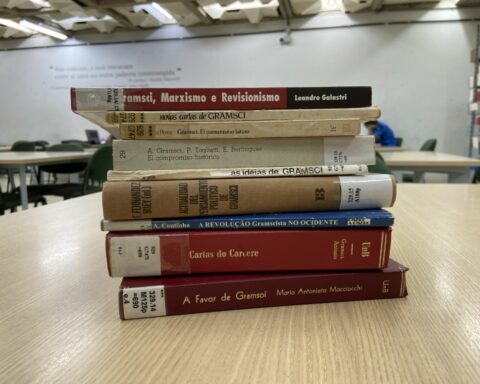

Deprived of his freedom and with few ways to contact the outside world, except for letters, newspapers and books he received in his cell, the newspaper articles he wrote previously no longer made sense. Therefore, Gramsci began writing thirty-three school notebooks that would later be published and known as Prison Notebooks. The idea, unlike texts written while free, was to produce a longer reflection.

The production of these texts, which dealt with various themes of history and politics, took place between 1929, when he received authorization to write in his cell, until 1935, when his health deteriorated. With a sentence that would last until practically the end of the 1940s, Gramsci was released in 1937. The release, far from being an act of humanity, was part of a political move by Mussolini. As the prisoner’s health worsened more and more, Mussolini feared that Gramsci would die in prison and become a kind of martyr.

Thus, at the time of Gramsci’s death, Mussolini published an article in the Corriere della Sera newspaper, stating that unlike the Soviet Union of Stalin, where prisoners were murdered, Gramsci had died in freedom. Cynicism that reveals the perversity of the fascist regime.

What did Antonio Gramsci think?

Despite being arranged in 33 school notebooks and dealing with various themes, Gramsci’s reflections were steered by some guiding threads. As a Marxist and communist, Gramsci sought to review the main concepts of Marx and Lenin in the face of the various historical transformations that occurred in the transition between the 19th and 20th centuries. In this sense, the Italian intellectual intended to demonstrate that the ideas of these communist leaders were elaborated from a reality that no longer existed in the 20th century.

The explosive revolution, such as the French one in the fall of the Bastille in 1789, no longer made sense in this new stage of modernity. With the emergence of political parties, unions and various forms of political association, political power was not centered on the State, but on civil society. Thus, any group that intends to govern society should mobilize its ideas and win the consensus of that society. For Gramsci, social changes are thought from the political dispute for hegemony in society.

Thus, the Brazilian far-right’s view of Gramsci is mistaken. It usually states that communism has a strategy of totalitarian domination that goes through the Machiavellian control of culture and that this is always done in hiding, manipulating people, like a conspiracy theory. This control would be a way to get to the revolution. But this is a simplification (or rather, a manipulation) of Gramsci’s concept. When the Italian thinker speaks of hegemony, he is not talking about any Machiavellian plan, nothing plotted in the dark, and nothing specific to communism. On the contrary: Gramsci’s concept of hegemony aims to show how this new politics that began to be done in the first decades of the 20th century works. The dispute for hegemony, that is, for the consensus of civil society, is not done in the shadows and does not aim at revolution. All social groups and all political ideologies express their interests and projects through various vehicles. In this sense, despite having entirely different positions, right-wing, centrist and left-wing organizations, in their various forms, are all disputing hegemony.

In addition to not being a diabolical practice, the theory of hegemony seeks to demonstrate how political power is created and legitimized in our time. People, from contact with various ideas and projects, create their worldviews and begin to support certain causes, leaders or parties. This development of individuals’ worldviews is not manipulation. People, after all, are not mere receivers of ideas. Through their culture, different individuals can agree or disagree, join or reject, or even comprehend in their own way ideas presented by an intellectual and political elite.

Politics, as well as the dispute for consensus, depends on how society deals to the different political projects in contest at specific moments. Depending on the correlation of political forces, society can lean towards the right or the left.

In the face of the dissemination of totally mistaken views, with clear authoritarian political intentions, it is important to assert the importance of authors like Antonio Gramsci. While in fascist prison, Gramsci never thought of communist indoctrination, but comprehended the functioning of politics and pointed to democracy as a purpose. Anyone who wishes to transform or conserve aspects of society, without resorting to authoritarianism and dictatorship, necessarily needs to contest hegemony. This is the greatness of Antonio Gramsci’s thought.

How to cite this article

OLIVEIRA, Marcus Vinícius Furtado da Silva. Who is afraid of Gramsci? In: Café Historia. Available at: ____________. Published on: __Dec. 6, 2023.

Tradução

Esse texto foi originalmente publicado em português. Tradução para o inglês de Tiago Imenes. Gostou desta tradução? Precisa de serviços de tradução? Conheça mais sobre o tradutor (que também é historidor) no site ProZ e solicite um orçamento. Ou entre em contato diretamente com ele por meio do e-mail: [email protected]. Traduções de Inglês>Português Brasileiro, Português Brasileiro>Inglês, Espanhol>Português Brasileiro.